Rain on a dark street in a big, bad city. A single cigarette ember, glowing in a room lit only by streetlights shining through venetian blinds. A bitter, cynical middle-aged man in a fedora and trench coat.

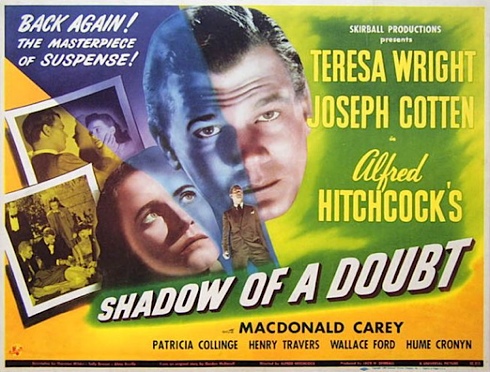

You won’t find any of these noir staples in Shadow of a Doubt, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1943 study of menace in a small town. (Except for the bitter, cynical middle-aged man. And he’s the villain.) Instead, the movie is drenched in sunshine, suffused with wholesomeness, and set in a small California town so close-knit that the traffic cop knows everyone’s name. Most of the action is filmed in a comfortable family home that could have been lifted right off the set of Meet Me in St. Louis. In fact, Sally Benson, the author of the original “Meet me In St. Louis” stories, co-wrote the screenplay, along with another great chronicler of small-town American life, Thornton Wilder.

And to top it all off, the heroine and sleuth is a teenaged girl.

Mild spoilers ahead.

But this is noir, no doubt about it. All the thematic elements are here: doubleness, dark secrets, stolen fortunes, femmes fatales (or their simulacrums), and even the requisite shadows through curtains. That the curtains are ruffled and filmy, the shadows barely noticeable unless you’re looking for them, is part of the point: just as the title hints, there are shadows aplenty in the world of Shadow of a Doubt. It’s just that no one wants to see them.

Young Charlie, the heroine, played with just exactly the right mix of ruthless hunger for life and starry-eyed self-absorption by Teresa Wright, certainly doesn’t. As the film opens, she can’t see much beyond the end of her nose. She’s just graduated from high school at the top of her class, and is restless and bored and desperate for something exciting to happen. She gets her wish, and then some, when her Uncle Charlie—her favorite relative, for whom she was named—shows up.

Young Charlie has kind of a thing for her uncle. “We’re like twins,” she tells him, adoringly, and their connection does indeed verge on the supernatural: when we first see Uncle Charlie (played by the suave and just-menacing-enough Joseph Cotten), he’s lying on a rooming-house bed in broad daylight, arms behind his head, staring at the ceiling. Young Charlie, in the first shot of her, is lying in exactly the same position in her frilly small-down bedroom. She gets the urge to telegraph him at just the same time that he wires the family to announce that he’s coming for a visit. And soon after her uncle arrives, Young Charlie begins humming a song she can’t stop hearing in her head, the “Merry Widow Waltz.”

Uncle Charlie really can’t stand that humming. Hmm could his sensitivity have something to do with the article he’s cut out of the family newspaper and thrown away or the mysterious initials engraved on the ring he gives Young Charlie or the way he’s given to rants about the evil vacuity of “fat, wheezing” women who can’t find anything better to do than spend their dead husbands’ money? Oh, Young Charlie, don’t tell your uncle you know a secret about him, even if you mean it in the nicest possible way! Can’t you see it freaks him out! You’re watching him way too closely, you know; you’re gonna find out things you wish you hadn’t!

Not surprisingly, the shadows tell you what’s going on in this movie. Mostly it’s Uncle Charlie who’s in shadow, just so we know who the bad guy is. But then there’s the moment, about three-quarters of the way through, when things shift: Uncle Charlie has heard a critical piece of good news and is bounding upstairs, having shaken off the forces pursuing him. The ominous music crescendos, when suddenly it cuts off, and in dead silence he turns around to look behind him. And from his point of view, we see Young Charlie, framed in the front doorway, at the foot of the stairs: a picture of wholesome girlhood, church hat in her hands, sunshine streaming all around her… and her long, dark shadow falling across the threshold.

Because, despite the charisma Joseph Cotten brings to his depiction of Uncle Charlie, this is really Young Charlie’s story, and her struggle: to decide whether she thinks her uncle’s a murderer, whether she’s going to turn him in, and finally, what she’s going to do to save herself. But underneath that is the question of what kind of person, what kind of woman, Charlie is going to be. There are examples all around her of what she doesn’t want to be like: her mother, who has so little identity of her own that she clings blindly to her brother as her only link to the young girl she once was; the town librarian a sterile shusher of the kind usually found in movies of this era; her high school friend Louise, now a waitress in a seedy bar, whose dead voice only comes alive when she’s admiring Charlie’s ring.

So what’s left for Young Charlie? What’s she to make of herself? She was, her father tells us, the smartest girl in her class, but school’s over now, and she doesn’t seem to have any kind of job or compelling passion on the horizon, not even a serious boyfriend. Jack, the detective on her uncle’s trail, has an interest in her, and there’s an edge of flirtation to his bullying when he admonishes her that “you’re a nice girl such a nice girl that you know you’d help me if you knew your uncle is the man we want.” But Charlie isn’t convinced that she is, or wants to be, a nice girl, or that she wants to be Jack’s girl, for that matter. She doesn’t know what or who she wants to be. And it’s her doubts about herself, as much as her growing suspicions about her uncle, that shadow her actions and her decisions.

The first time I saw Shadow of a Doubt, I was almost twenty-one: like Charlie, right on the edge of adulthood. (It comes later now than in 1943.) When, in the end, Charlie moves forward into adult life burdened but strengthened by her new understanding of life’s shadows, I grabbed onto that hopeful ending like a lifeline: Charlie learns who she is, and maybe I would, too.

Watching it ten years later, with a feminist sensibility, I remember feeling betrayed by the way Charlie shifts from dissatisfied questioning to loyal alliance with the forces of order and normalcy: she starts helping her mother around the house, gets engaged to Jack, learns to be content in her ordinary small-town life. Feh, I thought at the time: Hitchcock’s selling out women once again.

But this third time around, a dozen years later still, it seems clear to me that the romantic subplot is pretty perfunctory, and that the movie isn’t really about Young Charlie succumbing to the dreaded patriarchy: it’s about her diving into the complexity of life, and making agonizing decisions because she has to, and growing up through doing that. The shadows she begins to see aren’t just in her Uncle Charlie, or in the world at large, but in herself. Who Charlie ends up with isn’t really important; what matters is that she’s moved out of her uncle’s shadow, and is beginning to cast her own.

Els Kushner is a writer and librarian living in Vancouver, where you could film a nice rainy noir just about any day of the year except last week.